The Use and Symbolism of

Nichiren Buddhist Meditation Beads

by David Heimburg

Buddhists chanting beads or juzu (in Japanese) while meditating.

They were used for counting by early Buddhists, but the current

predominant and enduring use is as a tactile sensory focus and

stimulus while chanting. They have much symbolism and are an

important tool to use while meditating. Notice that I said "important"

not absolutely necessary. How important, though? Well, let me

put it this way, anything that enhances the effectiveness of

chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo is extremely important. The very

act of chanting is a significant ritual. During the chanting

meditation you strengthen and elevate your life condition. Access

to one's life condition is by means of your senses. Using the

beads engages an important one, the sense of touch. That's their

primary purpose and using them actually helps many people focus

better while chanting. As well, there is a lot of symbolism

of the beads that is meaningful for your meditative practice.

If you currently belong to a Nichiren Buddhist organization

other than Transcendent Life Condition Buddhism, you will be "discouraged" from using

meditation beads with tassels. Instead, you will be asked to

buy beads with ridiculous looking little pom-poms. Those other

Nichiren Buddhist organizations currently say that only priests

are "allowed" to use beads with tassels (or pom-poms

with extended tassels) because this denotes their "status

as teachers of the Law and to share their benefit." They

further explain that the balls or pom-poms that all people other

than priests must use symbolize the spread of Buddhism world-wide

(aka kosen rufu). The idea, I suppose, is that the pom-poms

extend their ends in every direction from the center, and this

indicates spreading Buddhism. Nice thought, until you consider

what "center" they're alluding to. Presumably it's

the sangha, which specifically means the group of monks and

nuns who renounced secular life and dedicated themselves to

Buddhist practice night and day but more generally includes

all Buddhist practitioners: monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen;

collectively, the grouping of all Buddhist practitioners. If,

in fact, that is what the pom-poms mean then why don't they

mean the same thing for priests who should be part of this sangha?

What they're really saying by enforcing the use of only pom-poms

for non-priests, is that priests are really special and should

be treated with more respect than you deserve.

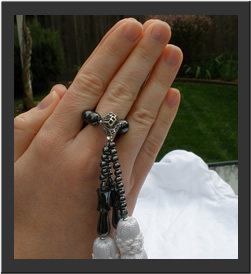

This is NOT a Transcendent Life Condition Buddhism priest.

This is Reverend Shiba, a Nichiren Shoshu priest, holding

his beads with tassels

Both Buddhists (laity & priests) should have the same

kind of Buddhist practice, according to Nichiren. He advocated

that there should "be no distinction" between those

who practice Buddhism, presumably referring to the thought that

there should be no distinctions of the status of each person

rather than differences in the personal mission of each. Priests

perform ceremonies such as weddings and funerals. Laity do not

(usually). Laity have more opportunity to talk with others about

Buddhism than priests do, and typically are more effective at

teaching Buddhism broadly within society.

There is a current point of view among some other Buddhist

organizations that Buddhism is best propagated by keeping

the roles of laity and priests distinct and separate. We of

Transcendent Life Condition Buddhism feel that while certainly there will be different personal

areas of emphases for as many individuals, whether they be

priests or laity, as there are, those who practice Buddhism

are not really different from each other at all in terms of

function and purpose.

Then there are people who choose not to directly teach Buddhism

to others but will instead invite friends to attend meetings

or attend their temple to hear a priest. There are still others

who just financially support the priesthood and in this way

consider their offerings as their practice for the accomplishment

of kosen rufu or world wide propagation of Buddhism. There

may be circumstances that people find themselves in which

make these methods the most viable and appropriate for them.

Some examples might be that you're living in a country in

which you don't speak the native language fluently yet. Or

you may have certain physical or mental illness that limits

your opportunity to engage with others socially and you therefore

have few opportunities to teach Buddhism. By using priests

or others' ability to teach Buddhism on your behalf, you can

still participate in the spread of Buddhism using these indirect

methods.

But if you are capable of teaching Buddhism to others you

should definitely do so. Teaching Buddhism becomes your arena

for developing your compassion, your Buddhahood. The more

you teach, and the more sincerely you teach, the more you,

in the process, will learn about Buddhism and about your own

path to the development of Buddhahood. Certainly it all starts

with your own practice of Buddhism. But almost immediately

your practice can include your own sincere efforts to teach

and encourage others as well. There's a quote from the Lotus

Sutra, "Teacher of the Law" (tenth) chapter, that

says: "… [O]ne who secretly teaches to another even

a single phrase of the sutra should be regarded as the Buddha's

envoy, sent to carry out his work." Nichiren teaches

that "a single phrase" can mean Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo.

That phrase is not only the title of the Lotus Sutra, it's

also the essence and meaning of the entire Lotus Sutra. So

teaching someone to chant Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo is teaching

Buddhism. The term envoy in the quote above, refers to a person

who acts as an agent for another. This signifies that teachers

are envoys of their own and others' Buddha nature and that

their own Buddha nature is revealed and brought out in the

act of compassionately teaching another person about Buddhism.

You're acting as an envoy of your own Buddha within. So being

a teacher of the law is not outside the grasp of everyone.

So for Transcendent Life Condition Buddhism members, each has taken vows to devote their

entire lives to the practice and study of Buddhism. In this

regard they are no different from priests (and some in fact

are priests). They accomplish the task of fulfilling their

vows while remaining within society. That is, they hold jobs,

raise families, and otherwise carry on normal lives.

There are various bead makers and vendors who sell both beads

with tassels and beads with pom-poms. Transcendent Life Condition Buddhism is the only Buddhist

organization today that encourages its members to use only

the tassel beads. But anyone, regardless of organizational

affiliation should consider using tassel beads. And they should

consider taking vows as well. In this way we hope to encourage

more and more individuals to become teachers of the Law and

individuals who are on the path to Buddhahood.

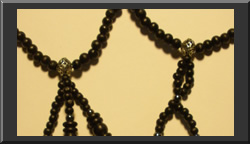

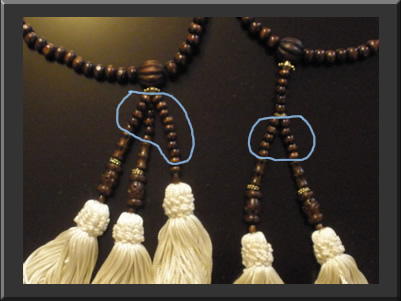

There

are five strands of beads that extend off from the main loop

or circle of beads. This is the most obvious distinction between

Nichiren Buddhists' beads and beads used by other forms of Buddhism

who typically use two end strands (or sometimes four) on their

beads. As you look at the various symbols of Nichiren Buddhist

beads, all of the symbolism used refers back to the individual

Buddhist practitioner and the relative significance of this

specific form of Buddhism. The following are some of the symbolic

reasons for using chanting beads with five strands instead of

the two used by other Buddhists.

If you lay out the beads on a table with a single

twist in the middle of the large circle, it's easy to see

how they give shape to a symbolic human. The three tassels

become a head and two arms. The twist in the large circle

of beads becomes a waist. The two tassels become two legs.

All of Buddhism relates back to the individual and the individual's

practice to eliminate all sufferings in both themselves and

others. All references of the symbolism of the chanting beads

to humans is significant and instructive. It's important to

always keep that in mind. It is never about a deity or external

power, rather it is about your subjective life and how to

transform yourself into a Buddha.

Centuries ago, Buddhists came up with the

hypothesis that each individual human being has come into

existence through the temporary uniting of five components.

The theory tries to describe both the physical and spiritual

aspects of human life. The five are: form, sensation, idea,

choice, and cognition.

- Form means the physical aspect

of life and includes the five sense organs - eyes, ears, nose,

tongue, and body - with which one perceives the external world.

- Sensation is the function of receiving external information

through the six sense organs (the five sense organs plus the

"mind," which integrates the impressions of the

five senses).

- Idea is the function of creating mental

images and concepts out of what has been perceived.

- Choice is the will that acts on the idea and motivates action.

- Cognition is the conscious function of discernment or reasoning

that integrates the components of sensation, idea, and choice.

Form represents the physical aspect of your life, while sensation,

idea, choice, and cognition represent the spiritual aspect.

Because the physical and spiritual aspects of life are inseparable,

there can be no form without cognition, and no cognition without

form.

All life carries on its activities through the interaction

of these five components. Their workings are colored by karma

previously formed and at the same time create new karma. We

acknowledge that these five components are coming together

in the moment we begin chanting.

The practice of chanting meditation is

an act of purification. The five impurities or defilements

is a concept that appears in Shakyamuni's "Expedient

Means" (second) chapter of the Lotus Sutra where it says,

"The Buddhas appear in evil worlds of five impurities…."

- Impurity of the age includes repeated disruptions of the

social or natural environment.

- Impurity of desire is the

tendency to be ruled by the five delusive inclinations, i.e.,

greed, anger, foolishness, arrogance, and doubt.

- Impurity

of living beings is the physical and spiritual decline of

human beings.

- Impurity of thought, or impurity of view,

is the prevalence of wrong views such as the five false views

(see next explanation).

- Impurity of life span is the shortening

of the life spans of living beings.

Simply put, this indicates

that our Buddhahood is made manifest amid the impurities of

whatever age we live in. There is no need to change all of

the evil in the world before we can attain happiness and enlightenment.

But at the same time we acknowledge that as we chant, the

five impurities influence us away from our goal of developing

the compassionate Buddha within.

The Buddhist scholar T'ien-t'ai (538-597)

of China held that there are five false views or ways of thinking

that give rise to desires. The five false views are:

- Though

the mind and body are no more than a temporary union of the

five components, one regards them as possessing a self that

is absolute; and though nothing in the universe can belong

to an individual, one views one's mind and body as one's own

possession.

- The belief in one of two extremes concerning

existence: that life ends with death (disregarding the vestigial

traces and historic influences), or that life persists after

death in some eternal and unchanging form (as an intact identity

of your former self).

- Denial of the law of cause and effect.

- Adhering to misconceptions and viewing them as truth,

while regarding inferior views as superior

- Viewing

erroneous practices or precepts as the correct way to enlightenment.

By utilizing the practice and study of Buddhism and by pursuing

scientific inquiry into natural laws that affect our lives,

we can change the five false views that we hold. As we chant,

when we recognize desires that arise in our minds as having

come from these five false views, we can adjust our way of

thinking and meditating. To always advance and continuously

correct erroneous views of life that we may find ourselves

settling for, we acknowledge that the study of life is a necessary

aspect of our Buddhist practice. The five false views reminds

us to diligently use scientific inquiry, Buddhist meditation,

and compassionate practice in order to remain on the path

to Buddhahood. This requires much humility, courage, and determination.

Nichiren (1222-1282) in his writing

titled The Opening of the Eyes developed the fivefold comparison

as a way of demonstrating the superiority of his teaching

of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo over all other teachings. The fivefold

comparison ranks teachings according to the effectiveness

of each at bringing about the enlightenment, that is, absolute

happiness and fulfillment, of the individual. To fully understand

these five comparisons, the reader is encouraged to read this

profound writing. The fivefold comparisons, briefly described

are:

- Buddhism is superior to non-Buddhist teachings. In Nichiren's

day in Japan, the common non-Buddhist teachings he was dealing

with were Confucianism and Brahmanism. He said that Confucianism

and Brahmanism are not as profound as Buddhism in that they

do not reveal the causal law of life that penetrates the three

existences of past, present, and future. Today, non-Buddhist

teachings abound and are well known, with Christianity, Judaism,

and Islam being the most prominent.

- Mahayana Buddhism is superior to Hinayana Buddhism (aka

Theravada). Hinayana (lesser vehicle) Buddhism is the teaching

for people of the two vehicles. These vehicles are the teachings

used by the so-called voice-hearers (Skt. Shr?vaka) and cause-awakened

ones (pratyekabuddha) to their respective levels of enlightenment.

The voice-hearers used the four noble truths; the cause-awakened

used the vehicle of causal relationship via the teaching of

the twelve-linked chain of causation. The pratyekabuddhas

lived apart from other humans, and along with the voice-hearers

were renounced by provisional Mahayana Buddhist's for seeking

their own enlightenment without working for the enlightenment

of others. In contrast, Mahayana Buddhism is the teaching

for bodhisattvas who aim at both personal enlightenment and

the enlightenment of others; it is called Mahayana (great

vehicle) because it can lead many people to enlightenment.

So in that sense, Mahayana teachings are superior to Hinayana

teachings.

- True Mahayana is superior to provisional Mahayana. True

Mahayana is defined by Nichiren as relating to the teachings

of the Lotus Sutra, while Provisional Mahayana refers to pre-Lotus

Sutra teachings. In the provisional Mahayana teachings, the

people of the two vehicles, women, and evil persons are excluded

from the possibility of attaining enlightenment; in addition,

Buddhahood is attained only by advancing through progressive

stages of bodhisattva practice over incalculable periods of

time. In contrast, the Lotus Sutra reveals that all people

have the Buddha nature inherently, and that they can attain

Buddhahood immediately by realizing that nature. Furthermore,

the provisional Mahayana teachings assert that Shakyamuni

attained enlightenment for the first time in India and do

not reveal his original attainment of Buddhahood in the remote

past, nor do they reveal the principle of the mutual possession

of the Ten Worlds, as does the Lotus Sutra. For these reasons,

the true Mahayana teachings are superior to the provisional

Mahayana teachings.

- The essential teaching of the Lotus Sutra is superior

to the theoretical teaching of the Lotus Sutra. The theoretical

teaching consists of the first fourteen chapters of the Lotus

Sutra, and the essential teaching the latter fourteen chapters.

The theoretical teaching takes the form of preaching by Shakyamuni

who is still viewed as having attained enlightenment during

his lifetime in India. In contrast, the essential teaching

takes the form of preaching by Shakyamuni who has discarded

this transient status and revealed his true identity as the

Buddha who attained Buddhahood in the remote past. This revelation

implies that the eternal condition of Buddhahood is an ever-present

potential of human life. This is called the essential teaching

and is superior to the theoretical teaching in that it points

to the ever-present potential for Buddhahood rather than Buddhahood

being considered merely a historic occurrence.

- The Buddhism of sowing is superior to the Buddhism of

the harvest. Nichiren got this comparison from T'ien-t'ai's

concept of sowing, maturing, and harvesting in his writing

The Words and Phrases of the Lotus Sutra. The seed being referred

to here is the seed cause for attaining Buddhahood.

Helping each other was a survival mechanism that early humans

had in order to endure the ravages of the environment as well

as competing animals and other competing human tribes. As

time passed, humans developed more cognitive capabilities

as well as more sophisticated tools and machinery that allowed

survival of individuals who had little concern for those outside

their family. The current age continues with this disconnecting

of humans from one another and interferes with the compassion

that is so necessary for Buddhahood to develop within our

lives. Surprisingly, though, when an individual does go against

the trend of the times and does develop compassion beyond

their family unit, that compassion is further-reaching than

their ancestors' compassion. Compassion that drives bodhisattva

caring in modern times tends to be a more universal compassion

than the clan-concerns of early times. Through better forms

of communication we've had individual lives who are no more

than remotely evolutionarily related to us brought to our

attention. We find ourselves weeping in concern for those

subjected to religious atrocities such as the beheading of

Islamic apostates and stoning of violators of Islamic sexual

codes of conduct. We see other species of animals suffering

from the effects of human corruption of their environment

and feel empathy and pity for them. We have learned to care

for other life without the expected reciprocation that our

predecessors hoped for when supporting others of their clan.

This caring or compassion when consciously evoked or strengthened

through the Buddhist practice of chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo

is vastly superior to the practices that preceded it that

involved family and ancestral lineages. This practice is limitless

and timeless. While there is no "bad" or inconsequential

amounts of compassion, and while all compassion supports the

development of one's Buddhahood, the more selfless caring

we can muster, the more powerful a force it becomes. In modern

times we are able to see beyond our immediate world and honestly

and passionately care about ending the suffering of all beings

around the world. This is an act of planting the seeds for

Buddhahood in our own lives, then nurturing that seed until

it matures. Finally, and within our own lifetimes, it is possible

to realize an end to our own suffering that is rooted deeply

in our compassion for many, many others. This is the highest

form of Buddhism and is called the Buddhism of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo,

the Buddhism of sowing.

In summary, people in this age don't believe that there is

any practice that will lead to enlightenment in this lifetime.

They have become jaded, lost hope, and don't focus their lives

on developing compassion and altruism, what's known as a bodhisattva

practice. Therefore they don't plant the seed for attaining

Buddhahood in their lives. In other words, they have no hope-seed

of Buddhahood in this lifetime. Nichiren described Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo

as the seed of Buddhahood that people of our times can implant

into their lives and in one lifetime mature and harvest it.

Ultimately, Nichiren says that there was nothing in the Lotus

Sutra or pre-Lotus Sutra teachings that can give realistic

seed-hope for the attainment of Buddhahood. The cause of the

bodhisattva practice is contained in chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo.

As Nichiren puts it in his writing titled The Teaching for

the Latter Day, "Now, in the Latter Day of the Law, neither

the Lotus Sutra nor the other sutras lead to enlightenment.

Only Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo can do so."

Notice

the two larger beads on the main loop of beads. These represent

objective reality (bead with two strands coming off it, held

on the left hand looped over the third finger) and subjective

wisdom (bead with three strands, held on the right hand over

the third finger).

The concept of the fusion of objective reality and subjective

wisdom is analogous to the process of attaining Buddhahood.

It considers that there exists truth, or objective reality,

and that this truth can be obtained or realized subjectively

through the development of our compassionate wisdom. It further

posits that objective reality is otherwise known as the law

or principle of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo. By fusing the subjective

law of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo by chanting it and thereby subjectively

"activating" it, with the external law of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo

in its environmental reality, each individual can gradually

attain Buddhahood.

This

relationship of self to objective reality is also represented

by Shakyamuni Buddha (subjective wisdom) on the right hand and

Many Treasures (aka Taho) Buddha (objective reality) on the

left hand. The historical existence of Shakyamuni Buddha who

developed the subjective wisdom that enabled him to become a

Buddha symbolizes the same potential in each one of us to manifest

that wisdom with our Buddhist practice. The mythical existence

of Many Treasures Buddha first appeared in the "Treasure

Tower" (eleventh) chapter of the Lotus Sutra. The fusion

of Shakymuni and Many Treasures Buddha represents the application

of wisdom to the objective world, the application of an enlightened

perspective on natural phenomena. While the objective world

remains the same, our spiritual relationship to it can be either

positive and fruitful or negative and destructive. Many Treasures

Buddha represents the concrete outcome or result of happiness

within reality. That is, it is happiness amid the reality of

life in all its manifestations. This affirms that the inevitable

result of chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo with great subjective

compassion results in happiness within our present lifetime.

These two beads are also sometimes referred to as the "parent

beads". This is another symbolic and analogous representation

of the process of offering our subjective compassion and love

while chanting and having that cause result in giving birth

to or obtaining the result of happiness that's been thereby

awakened within our lives. We remind ourselves that unconditional,

parental compassion for other living beings is just the kind

of compassion that we attempt to summon up in our practice of

chanting. It is the kind of compassion that led Shakymuni, in

the "Life Span" (sixteenth) chapter of the Lotus Sutra,

to declare "I am the father of this world, saving those

who suffer and are afflicted."

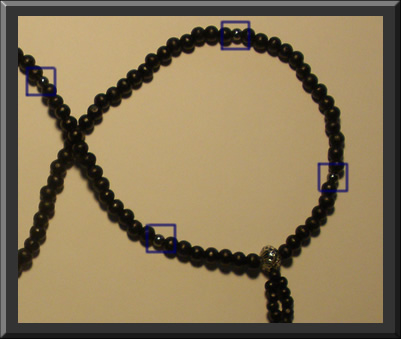

The

main loop of beads is made up of 108 beads (interspersed with

four smaller "bodhisattva beads" which will also

be explained) which represent all categories of ways that

desires affect us at any given moment.

The

main loop of beads is made up of 108 beads (interspersed with

four smaller "bodhisattva beads" which will also

be explained) which represent all categories of ways that

desires affect us at any given moment.

This number is derived at by the following calculations:

(1) Six senses are the main means by which desires affect

us. These are analogous to the sense of sight, hearing, smell,

taste, touch, and the mind that receives sensory input.

(2) Six senses are multiplied by the three aspects of time:

past, present, and future. [6 senses x 3 aspects of time =

18 aspects of desire]

(3) Two characteristics of good or evil intent within our

mind affect our desires. Good intent is associated with desires

that benefit ourselves or others or society at large, while

evil intent relates to the desire to cause deliberate harm

to another or to society. [18 aspects of desires x 2 kinds

of intent = 36 aspects of desire]

(4) Three levels of attention or preferences that we have

at any moment affect our desires. We can like (intend to act

on), dislike (intend to not act on), or be indifferent to

(momentarily ignore) any of the multitude of desires that

bombard us at any given moment. We tend to quickly rank our

desires within these categories and thereby multiply the affect

of any of the 36 aspects calculated thus far. [36 aspects

of desires x 3 levels of preference = 108 aspects of earthly

desires]

Early Buddhists perceived the connection between desires and

suffering. There's a direct connection. So their early attempts

were to use ascetic practices to cut off their desires and

thereby eliminate suffering. These were some of the first

crude attempts at attaining Buddhahood or the elimination

of suffering. The logical errors contained in such efforts

finally dawned on those who attempted to deprive themselves

of sexual relations, family and social relationships, and

even food and drink. Extinguishing all desires in order to

attain enlightenment would paradoxically include the desire

for enlightenment itself and even the desire to live. It's

clear to us that such efforts are futile and foolish to the

point of absurdity.

The Mahayana teachings deal with earthly desires entirely

differently than the Hinayana (early) teachings do. Hinayana

teachings held that earthly desires and enlightenment are

two independent and opposing factors, and the two cannot coexist.

Mahayana teachings turn that Hinayana principle over and say

that earthly desires cannot exist independently on their own;

therefore one can attain enlightenment without eliminating

earthly desires. Mahayana Buddhist teachings say that these

108 categories of earthly desires are actually one with and

inseparable from enlightenment. This is because all things,

even earthly desires and enlightenment, are manifestations

of the unchanging reality or truth - and thus are non-dual

at their source.

So from a practical standpoint, we still acknowledge the harmful

effects of giving ourselves over to desires. Through the means

of fusing our subjective wisdom with objective reality (as

symbolized with the two large beads) we come to transform

our harmful desires while maintaining the supportive ones

that allow us to fully embrace our lives as well as the suffering

lives of others. With the compassionate meditative practice

of chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo, our overriding desires for

the happiness of others become directly connected to and result

in our own attainment of Buddhahood. As Nichiren put it, "Today,

when Nichiren and his followers recite the words Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo,

they are burning the firewood of earthly desires, summoning

up the wisdom-fire of enlightenment."

If you look among the 108 beads in the main loop you'll see four

different sized and sometimes different colored beads. These

four beads represent the four leaders of the bodhisattvas of

the earth. These bodhisattvas represent characteristics that

you acquire as a result of chanting and teaching Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo.

In the "Emerging from the Earth" (fifteenth) chapter

of the Lotus Sutra, Shakyamuni tells a story about the earth

splitting open and bodhisattvas in countless numbers coming

forth. Their bodies are golden and they possess the thirty-two

features that characterize a Buddha. They are led by four bodhisattvas

- Superior Practices, Boundless Practices, Pure Practices, Firmly

Established Practices - and Superior Practices is the leader

of them all. This analogy was used to indicate the bodhisattva

practice of compassion that directly leads to Buddhahood.

As an aside, it's interesting to note that the question as to

where these four bodhisattvas came from and who they are led

straight to the "Life Span" chapter, considered to

be the heart of the Lotus Sutra and a description of enlightenment.

In other words, even in the construct of the text of the Lotus

Sutra, the four bodhisattvas led the way to the highest stage

of enlightenment.

The four bodhisattva leaders signify the Buddha conditions or

virtues of

- true self

- eternity

- purity

- happiness

These four bodhisattvas, or aspects of Buddhahood, are associated

explicitly with the Lotus Sutra, and more specifically with

the teaching of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo. These four bodhisattvas

are said to be so much superior to the bodhisattvas associated

with other Buddhist teachings that the other bodhisattvas, although

seemingly magnificent and wonderful in isolation, pale by comparison

to Superior Practices, Boundless Practices, Pure Practices,

and Firmly Established Practices. Nichiren likens the comparison

to a scene in which humble mountain folk are seen mingling with

nobles or humble fishermen appear in an audience before the

emperor. Such a statement is obviously intended to suggest the

superiority of the results attained from a Buddhist practice

based on these four principles.

True self, eternity, purity, and happiness are both the leaders

of all people to the enlightenment of the Lotus Sutra as well

as descriptions of the kind of enlightenment attained by this

practice. We can use them as guides for our desired state of

mind as we chant - in other words, objects of focus.

True self refers to the Buddha nature within, the Buddha you.

Eternity refers to the eternal aspect of the Buddha nature inherent

within all things and the eternal aspect of yourself. In essence,

it means that all things have the potential to become Buddhas

or lead others to enlightenment. This potential lies eternally

dormant, in potentia, throughout the whole of the universe (or

universes). As one cannot be totally fulfilled and happy while

others suffer, Buddhas don't exist outside of their struggle

to lead others to enlightenment.

In practice, all four bodhisattvas are related to compassion.

After all, they are all bodhisattvas, representatives of the

life condition of bodhisattva, the internal condition of compassion.

Superior Practices can be said to symbolize the unswerving determination

to save all others from suffering. It is a self-confidence grounded

in compassion that leads all others to Buddhahood. In his writings,

Nichiren refers to himself as Bodhisattva Superior Practices

incarnate.

Boundless Practices relates to the enduring life condition of

Buddhahood which results from a vow and commitment to the bodhisattva

practice of compassion. Pure Practices describes the process

of purification that results from devoting oneself to the bodhisattva

practice of compassion for all species, and indeed all living

beings. When we internalize the reality that we are an aspect

of the universe, as one's view of "self" expands to

incorporate all of the natural world, caring and concern for

others progresses to include more and more individuals of various

species. The life condition that results is thereby purified

to include a broader and broader definition of self. Conversely,

being only concerned about selfish desires pollutes the flow

of one's practice and leads to stagnation. Firmly Established

Practices describes the condition where happiness continuously

arises within a person who devotes their entire life to establishing

a compassionate bodhisattva practice.

The placement of the four bodhisattva beads among the 108 desires

has important symbolism. If we are to effectively deal with

our desires, we must develop other, freeing and noble, aspects

of ourselves. As we chant, true self, eternity, purity and happiness

naturally surface and give rise to the development of caring

and compassion for others. This is the place where your hands

touch together. This is where the action is. Knowing theoretically

that the fusing of subjective wisdom and objective reality leads

to Buddhahood is not the same as actualizing or realizing it.

In order to realize Buddhahood one must commit to the attainment

of these four aspects of our lives and become more compassionate

by means of a bodhisattva practice. There is no need to isolate

oneself from others or even from our own desires. The four bodhisattva

characteristics, as symbolized by the four small beads, remind

us that we need to determinedly vow to put ultimate meaning

and significance into our own lives.

If you look at the left hand Many Treasures bead, the one with

two long strands extending from it, you'll notice a small circle

of ten beads. These ten beads symbolize the mutual possession

of the Ten Worlds or ten life conditions that a person can exhibit

at any given moment. This categorization of life condition is

a component principle of three thousand realms in a single moment

of life, which T'ien-t'ai (537-597) established in his work

titled Great Concentration and Insight. The important aspect

of this principle is that the World of Buddhahood or enlightenment,

is found within the reality of our lives in the other nine Worlds,

not somewhere separate. This is why the Ten Worlds bead circle

appears on the left or "Objective Reality" side of

the beads. The mutual possession of the Ten Worlds is also symbolized

by the touching together of our ten fingers while using the

beads.

Here is a brief explanation of the Ten Worlds.

Hell indicates a condition in which living itself is

misery and suffering, and in which, devoid of all freedom, one's

anger and rage become a source of further self-destruction.

A condition governed by endless desire

for such things as food, profit, pleasure, power, recognition,

or fame, in which one is never truly satisfied.

It is a condition driven by instinct and lacking

in reason, morality, or wisdom with which to control oneself.

In this condition, one is ruled by the "law of the jungle,"

quivering in fear of the strong, but despising and preying upon

those weaker than oneself.

It is characterized by persistent, though not necessarily overt,

aggressiveness. It is a condition dominated by ego, in which

excessive pride prevents one from revealing one's true self

or seeing others as they really are. Compelled by the need to

be superior to others or surpass them at any cost, one may pretend

politeness and even flatter others while inwardly despising

them.

In this state, one tries to

control one's desires and impulses with reason and act in harmony

with one's surroundings and other people, while also aspiring

for a higher state of life.

This is a condition of contentment

and joy that one feels when released from suffering or upon

satisfaction of some desire. It is a temporary joy that is dependent

upon and may easily change with circumstances. These six worlds

are called the six paths.

Beings in the six paths, or those

who tend toward these states of life, are largely controlled

by the restrictions of their surroundings and are therefore

extremely vulnerable to changing circumstances. The remaining

four states, in which one transcends the uncertainty of the

six paths, are called the four noble worlds:

In this state, one dedicates oneself to creating a

better life through self-reformation and self-development by

learning from the ideas, knowledge, and experience of one's

predecessors and contemporaries.

In this condition one perceives the impermanence of all phenomena

and strives to fee oneself from the sufferings of the six paths

by seeing some lasting truth through one's own observations

and effort. People in the worlds of learning and realization

are given more to the pursuit of self-perfection than to altruism.

The world of bodhisattva is a state of compassion in which

one thinks of and works for others' happiness even before becoming

happy oneself. The term bodhisattva consists of bodhi (enlightenment)

and sattva (beings), meaning a person who seeks enlightenment

while leading others to enlightenment. The condition of bodhisattva

is an awareness that the way to self-perfection lies only in

altruism, working for the enlightenment of others even before

their own enlightenment.

The world of Buddhahood is characterized

as a state of perfect and absolute freedom in which one realizes

the true aspect of all phenomena or the true nature of life.

One can achieve this state by manifesting the Buddha nature

inherent in one's life. Attaining this condition does not mean

becoming a special being, separate from the other conditions

of life. Mutual possession of the ten worlds indicates that

within each of the other nine worlds the world of Buddhahood,

or tenth world, can manifest itself. In this state one still

continues to work against and defeat the negative functions

of life and transform any and all difficulties into causes for

further development. It is a state of complete access to the

boundless wisdom, compassion, courage, and other qualities inherent

in life; with these one can create harmony with and among others

and between human life and nature.

On

the long tassel strands there are thirty more beads remaining

that have not yet been discussed. On the ends with two strands

there are five beads each, and on the end with three strands

there are five beads on two of them and ten beads on the remaining

one. (These beads are far easier to observe than explain their

location.) This is a complex philosophical system established

by T'ien-t'ai (538-597) of China. The theory states that three

thousand realms, or the entire phenomenal world, exists in

a single moment of life. A "single moment of life"

is also translated as one mind, one thought, or one thought-moment.

The number three thousand comes from the following calculation:

10 (ten worlds) x 10 (ten worlds - within the previous ten)

x 10 (ten factors) x 3 (three realms of existence) = 3000.

Life at any moment manifests one of the ten worlds. Each of

these worlds possesses the potential for all of the ten within

itself, and this "mutual possession," or mutual

inclusion, of the ten worlds is represented as 10 x 10 = 100

possible worlds. Each of these hundred worlds possesses the

ten factors, making one thousand factors or potentials, and

these operate within each of the three realms of existence,

thus making three thousand realms.

The ten factors are descriptions of spiritual aspects of life

or reality. They are:

Attributes of things

discernible from the outside, such as color, form, shape,

and behavior.

The inherent disposition or quality

of a thing or being that cannot be discerned from the outside.

T'ien-t'ai also refers to the "true nature," which

he regarded as the ultimate truth or Buddha nature.

The essence of life that permeates and integrates appearance

and nature.

[These first three factors describe the reality

of life itself. The next six factors explain the functions

and workings of life.]

Life's potential energy.

The action or movement produced when life's

inherent power is activated.

The cause

latent in life that produces an effect of the same quality

as itself, i.e., good, evil, or neutral.

The

relationship of indirect causes to the internal cause. Indirect

causes are various conditions, both internal and external,

that help the internal cause produce an effect.

The effect produced in life when an internal cause

is activated through its relationship with various conditions.

The tangible, perceivable result that

emerges in time as an expression of a latent effect and therefore

of an internal cause, again through its relationship with

various conditions.

The unifying factor among the ten factors. It indicates

that all of the other nine factors from the beginning (appearance)

to the end (manifest effect) are consistently and harmoniously

interrelated. All nine factors thus consistently and harmoniously

express the same condition of existence at any given moment.

An analysis of the nature of a living entity in

terms of how it responds to its surroundings.

The individual living being, formed of a

temporary union of the five components, who manifests or experiences

any of the ten worlds.

The

place or land where living beings dwell and carry out life-activities.

The state of the land is a reflection of the state of life

of the people who live in it.

A land manifests any of the

ten worlds according to which of the ten worlds dominate in

the lives of its inhabitants. These three realms are not to

be viewed separately, but as aspects of an integrated whole,

which simultaneously manifests any of the ten worlds.

A single moment of life means life as an indivisible whole

that includes body and mind, cause and effect, and sentient

and insentient things. A single moment of life is endowed

with the three thousand realms or possibilities within it.

Nichiren advocated that by chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo one

can "see" or observe the existence of the realm

of Buddhahood within their own life and within the lives of

others from among any other of the possible realms.

On the ends of four of the five strands you'll find tube or jar

shaped beads. These signify vessels to accumulate fortune through

one's practice of chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo. They have a

pass-through hole for the tassels to be attached, and this is

indicative of the flow of Buddhahood. Attaining Buddhahood is

a process rather than a point in time. As you chant and develop

your bodhisattva practice of compassion for others, the merits

of your efforts accumulate in your life. Sometimes, you're so

focused on helping others attain Buddhahood you scarcely notice

your own happiness that has resulted from such efforts. But

whether you notice it or not, happiness does begin to build

up from the very first moment you begin your practice of chanting

meditation. But this happiness is not a static state. It is

more akin to a flowing river the current of which is determined

by your efforts to practice Buddhism. Happiness, thus built

up, is difficult to extinguish and is commensurate with your

own efforts to give it to others.