Nichiren Buddhism is a form of Mahayana

Buddhism named after the Japanese priest Nichiren, who devoted his

life to the enlightenment and happiness of the entire universe.

His basic story is similar in a couple of respects to the

historical Buddha credited with the original teachings of

Buddhism. Concerned with the suffering of the people all

around him, he dedicated years of his life to seeking a

way to eliminate their suffering. Once discovered, he made

a bold vow to teach this philosophy to others, even under

threat of losing his own life in the process. Due to his

strong determination to eliminate the suffering of others,

Nichiren became a Buddha. After all, that is what a Buddha

is -- a person who carries out a determination to eliminate

suffering from people's lives. Today, the members of Transcendent Life Condition Buddhism

are following in Nichiren's path; the path of every Buddha.

That is, we're committed to finding and using ways to eliminate

others' sufferings.

Every time I read [Nichiren] Daishonin’s writings, rather than simply trying to understand his words,

I seek to come into contact with his immense compassion, his towering conviction, his ardent spirit

to aid and protect others, and his solemn and unswerving commitment to kosen-rufu. Whenever I read his writings,

his radiant spirit, like the midsummer sun at noon, floods my heart. My chest feels as if it is filled with a

giant ball of molten steel. Sometimes I feel like a scalding hot spring is gushing forth inside of me, or as if a great,

earthshaking waterfall is crashing over me.

The name Nichiren was one that he took upon dedicating his life to the sole propagation of the Lotus Sutra.

The name means sun (nichi) lotus (ren).

Nichiren is often referred to as Nichiren Daishonin (Fuji Branch)

or Nichiren Shonin (Minobu Branch).

Daishonin is an honorific title. Dai means “great.” Shonin means “sage.”

Nichiren, named Zennichi-maro at birth, was born in Japan in 1222.

At that time, T’ien-t’ai Buddhism, called Tendai in Japan, was one of the most popular schools of Buddhism,

along with Shingon (True Word), Nembutsu (Pure Land), and Zen.

It was common at the time for a family to send one of their sons to a temple, as a sort of offering, to study Buddhism.

This was also the only way most children could receive an education at the time. Although there were schools in medieval Japan,

they were reserved for the nobility.

At the age of 11, Nichiren’s parents sent him to the Tendai temple, Seicho-ji, where he studied under a priest named

Dozen-bo. When he was 15, he was ordained into the priesthood.

When someone became a priest, they would change their

name to mark the transformation. Nichiren took the name

Zesho-bo Rencho.

When his initial training was complete, Nichiren determined to independently delve more deeply into the study of Buddhism

by visiting various temples around Japan and studying the array of Buddhist teachings available to him. He traveled the country,

going from temple to temple, to read the works contained in their libraries and engage with other priests. In his writings,

Nichiren displays a familiarity with not only Buddhist philosophy but also non-Buddhist philosophy, including such teachings as

Brahmanism, Confucianism, Asceticism, Taoism, and Shinto.

One of the things T’ien-t’ai was famous for, maybe the thing he was most famous for, was ranking of Buddhist philosophy from worst

to best, or from shallow to deep, or to put it more bluntly, from less correct to more correct. It was thought that the common

masses could not understand the deeper teachings and had to instead rely on the shallower teachings, while only priests and those

with greater understanding and abilities could delve into the deeper philosophies.

Nichiren employed T’ien-t’ai’s idea of ranking religion in his writings throughout his life,

ranking all religious teachings, Buddhist and non-Buddhist on a scale together from worst to best.

As we know, Nichiren finally decided that the Lotus Sutra was the best teaching of them all.

This ranking system was probably the least controversial thing he taught, because many other Buddhist leaders had already

accepted the notion of ranking religions (an idea that’s foreign to us), employed T’ien-t’ai’s ranking system, and had agreed

with T’ien-t’ai that the Lotus Sutra was supreme.

So what was different about the way Nichiren approached Buddhism? A few things were different.

One was that Nichiren thought everyone, not just priests, could practice, if not comprehend, the deepest teachings,

namely the Lotus Sutra. The second thing was that Nichiren came up with a practice, chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, that

everyone, regardless of intellectual ability, could use to understand the true depth of the Lotus Sutra, their Buddha nature

within. The third thing is that Nichiren figured that if there is a best teaching, and everyone can practice that teaching,

there’s no reason anyone should practice other teachings. Others prior to Nichiren had not arrived at any of these conclusions.

We have a problem with the propagation of religion. If we teach only the esoteric version of religion,

the religion can’t spread, because the majority of people can’t comprehend the depths of it.

If we teach only the exoteric version of a religion, the religion will be so dumb as to not merit

even an inkling of consideration by the more intelligent elements of society, and it will be quickly

and easily debunked by nearly every leader and thinker. To deal with this problem, even within a single religion,

esoteric and exoteric teachings are often combined together and one or the other version will be employed depending

on the circumstance and context.

Taking an example from Pure Land Buddhism (Jpn Nembutsu), a more exoteric interpretation of Pure Land

would hold that the Pure Land is literally a place you go to when you die if you pray to Amida Buddha.

A more esoteric view would hold that Amida is a metaphor and that the Pure Land refers to Buddhahood within.

Let’s use the more familiar example of Abrahamic theism. An esoteric description of the Abrahamic God holds

that God is “the inexhaustible depth and ground of all being.”

An esoteric Christian can hold to that

description of God on the one hand while praying to the more exoteric version of God, the

personified, cognizant being, and speak of his views and personality, on the other. They speak of Him saving,

punishing, forgiving, loving, judging, gracing, blessing, talking, listening, even impregnating as part of their

exoteric philosophy.

More than identify exoteric and esoteric interpretations of the same teachings, T’ien-t’ai identified

and separated exoteric sutras from esoteric sutras, arguing that the esoteric were the greater sutras.

Of course the Lotus Sutra fell into the superior esoteric category and was further identified as the best of them.

Though this ranking was widely understood and accepted, not everyone practiced Lotus Sutra Buddhism. This was the

state of Buddhism when Nichiren arrived on the scene in Japan.

It’s important to stop here and note that when I speak of exoteric and esoteric,

I do it in the general sense and not the specific sense. While the Lotus Sutra is

considered an esoteric Buddhist doctrine in the general sense, and in the sense of T’ien-t’ai’s

ranking system, True Word (Jpn Shingon) has claimed the title of “esoteric Buddhism” due to

the fact that the people of Japan employed the use of it for its esoteric practice.

By the time Nichiren was born, True Word was already referred to as “esoteric Buddhism”

simply because of the particular practice they employed. I will explain this a bit more further down.

The priests of Nichiren’s era, while generally agreeing with the supremacy of the Lotus Sutra,

argued that it was too difficult for the common people to grasp. Even Tendai priests,

those of Nichiren’s own school, felt this way. They thought the Lotus Sutra was a teaching

for a select class of people.

After Nichiren was ordained, while he was traveling the country in his pursuit of Buddhist understanding,

he came to reject the idea that the lesser teachings were necessary, at least anymore. He came to

believe that people could practice the teachings of the Lotus Sutra directly, without having to filter

those teachings through the lens of shallower teachings. And more than that, he determined that the lesser

teachings were obstructing people’s growth and interfering with their understanding of and adoption of the deeper,

truer teachings. In other words, the inferior teachings were a source of confusion for the people.

When he presented his argument, he had to present it through the lens of Buddhist scripture.

He was about to contradict contemporary leaders of Buddhism and the popular thinking of society.

Especially in Japan at that time, one could not simply state an opinion as one’s own and expect to be taken seriously.

He had to find substantiation for his points of view from within the Buddhist scriptures themselves.

He made his case using two main arguments:

-

The first argument I’ll present, due to its simplicity, was that Shakyamuni said it first:

“Honestly discarding expedient means, [I] will teach only the unsurpassed

way.” Although

I list it first, this was not his primary defense.

-

The other argument he used, his main argument, involved a prophesy of Shakyamuni’s.

Shakyamuni had made a generalized observation (one might call it a prediction) about

the way societies develop. First they have to learn things like art and music and become

generally civilized people. At that time people also develop societal standards and important works

of secular writings that shape the society. People live by the cultural norms created through this

process, although the collection of such norms and codes of conduct wouldn’t necessarily be

considered religions in the common sense of the word. In the next phase of societal development,

according to Shakyamuni, people learn non-Buddhist religious philosophies. After they’ve been able

to grasp non-Buddhist philosophies, they can then grasp the simplest level of Buddhist philosophy.

After that, they can understand the truest Buddhist philosophy, or the Lotus Sutra.

The last time period described, the time when the people are able to comprehend the Lotus Sutra,

is called the Latter Day of the Law (Jpn Mappo), a time when the people are jaded and corrupt, on

the one hand, but also able to understand the most difficult-to-grasp ideas. In this time period,

people are not only capable of grasping the true teaching of Buddhism, but, because they’re so deeply

corrupt at this point, they can only attain enlightenment through the very highest teaching, meaning the

Lotus Sutra. Nichiren argued that the time period he and his contemporaries were living in was the beginning

of Mappo, when the Lotus Sutra could and should be spread to the people.

One of the things Nichiren did while he was away from his home temple was to formulate and substantiate that

this was the time period in which the Lotus Sutra should reign over all other Buddhist teachings, without

entanglement with other Buddhist teachings.

Which theory to teach wasn’t Nichiren’s only problem. In addition to the matter of difficulty of the Lotus Sutra,

he also had to contend with the assertion that the Lotus Sutra didn’t have a corresponding meditative practice.

T’ien-t’ai had formulated a practice called “concentration and insight.” It was argued that though it

was philosophically correct, very few could actually do it, if anyone.

It was initially claimed that the lack of an accessible spiritual practice was the biggest hindrance of

propagating the Lotus Sutra directly to the masses. However, it’s interesting to observe that when Nichiren

removed this problem, the priests of his time largely still refused to discard the lesser sutras and propagate

the Lotus Sutra. So maybe the claim that there was no suitable practice was simply an excuse to cling to the

other sutras when they had no other reason to do so.

To deal with the fact that the Lotus Sutra didn’t have a widely-accepted practice, Tendai priests taught

practitioners to practice True Word (Jpn Shingon) practices and sometimes Pure Land (Jpn Nembutsu) practices.

Shingon and Nembutsu both use mantras, so to Nichiren, it was only natural that his replacement of those

practices be a mantra. Shingon Buddhists recite a phrase in honor of Mahavairochana Buddha. Nembutsu Buddhists

recite a phrase in honor of Amida Buddha, specifically, “Namu Amida Butsu.”

All Nichiren had to do was try to come up with a mantra that would embody the essence of the Lotus Sutra

to replace the mantras referring to mythical Buddhas from other, less profound, sutras. It seems like an

obvious improvement in retrospect, but for some reason no one had done it, even after hundreds of years of

debate about this very issue, until Nichiren arrived on the scene.

As we know, Nichiren arrived at the conclusion that the title of the Lotus Sutra was both its deepest

element and its symbolic banner. With the popularity of the Nembutsu chant, Namu Amida Butsu, the word

Namu was readily at hand to place before the title of the Lotus Sutra.

Far removed from the climate and culture of Buddhist Japan, I can spin the creation of this new mantra

as only the most sensible next step for Lotus Sutra Buddhism. But for Nichiren to assert the propagation of a

wholly new meditative practice was a daring move. He would spend his life defending it.

In 1253, when Nichiren was 31, he returned to his home temple of

Seicho-ji.

Nichiren was scheduled to speak at the temple about what he’d learned on his long study excursion.

It seems that Nichiren himself considered this an auspicious occasion, because it was on this date

that he changed his name from Zesho-bo Rencho to Nichiren. Nichi means “sun.” Ren means “lotus.”

So Nichiren means “Sun Lotus.”

On April 28th, 1253, priests and townspeople gathered at the temple to hear his

sermon.

We don’t know what exactly Nichiren said in this sermon, but we can surmise what

it might have been given his point of view and the response to the lecture. We might

surmise that in the sermon, explaining the conclusions he’d drawn from his years of study,

that the Lotus Sutra was superior to the other sutras, that the other sutras were a

source of confusion, and that, rather than practicing the teachings of other schools of

Buddhism, one should simply chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, his newly minted Buddhist practice.

Nichiren was an intellectual at heart. He had spent most of his early life in libraries and

temples. From his perspective, the assertion that the Lotus Sutra was supreme was merely a

matter of reasoning. He hadn’t been the first to say it. Many teachers that had come before him

had already made this point. It was the basic premise of his own school of Buddhism at that time,

Tendai, and still is in fact.

What was different for Nichiren was that part of his logic was that you can’t go backward,

only forward. In other words, once a superior teaching had been spread, it made no sense to

him why anyone would bother practicing an inferior teaching. He posed the question: if everyone

agrees that the Lotus Sutra is the best, why would we practice anything else? As Daniel B Montgomery

puts it in his book Fire in the Lotus, “Nichiren…was transforming the Round Teaching of

Tendai (‘round’ here means ‘perfect’) into a spearhead.”

To him this wasn’t a matter to be angry about but rather to simply accept rationally.

But his assertion of this principle meant that it was wrong to practice all of the religions

everyone in the country was already practicing. Anyone with experience in the world outside of

academia can see where this message might fall on deaf ears.

In medieval Japan, there wasn’t a clear separation of church and state. Theoretically there was freedom of religion,

but in practice government leaders could use their power to oppress and persecute practitioners of religions that

angered them.

Word of his sermon spread to the steward of the region, Tojo Kagenobu, who was a Nembutsu

Buddhist.

Kagenobu clearly didn’t appreciate something Nichiren said, maybe that the teachings and practice of

Nembutsu were inferior. Whatever it was, it must have struck a nerve, because Kagenobu attempted to have

Nichiren arrested.

Fortunately, Nichiren’s teacher, Dozen-bo, protected him and whisked him away to safety

out of Kagenobu’s grasp.

Apparently whatever Nichiren said was not only upsetting to Kagenobu but was also unacceptable

either religiously or socially or both to his own temple, because, though Dozen-bo protected

Nichiren from Kagenobu, he also expelled Nichiren from the order.

Nichiren was no longer an official Tendai priest as of that day.

After being nearly arrested, Nichiren went to Kamakura, the capital of Japan at that time,

determined to get his message out to the people and to the government. Nichiren lived in a hut

on the outskirts of Kamakura and “became a street corner evangelist.”

He lived his life this way for the next seven years. He made a few converts at the time,

notably Shijo Kingo, Nikko, Nissho, and Nichiro.

Shijo Kingo was a samurai who wrote Nichiren so many letters and stood so staunchly by Nichiren’s

side throughout the many trials in his life that he has come to be known, almost personally,

by Nichiren Buddhists everywhere. It’s nearly impossible to have any familiarity with Nichiren’s

writings without knowing Shijo Kingo as well.

Nikko is less well-known to us than Shijo Kingo was, because Nikko never wrote Nichiren. He never had to.

He was instead always at Nichiren’s side. While at Jisso-ji temple doing research for a seminal writing,

the Rissho Ankoku Ron (which will be discussed shortly), he met the twelve-year-old acolyte, Nikko,

who was so impressed by Nichiren that he became his disciple.

Nikko, Nissho, and Nichiro would become three of the six senior priests of Nichiren’s

priesthood who would inherit Nichiren Buddhism upon Nichiren’s death. Nikko would ultimately

split from the group following Nichiren’s death, thus dividing Nichiren Buddhism into two major

branches which still exist to this day, the Minobu school, originally founded by Nichiren with all

of the six senior priests at its head, and the Fuji school, founded by Nikko. Transcendent Life Condition Buddhism considers itself

to be of the Fuji school lineage and philosophy. SGI and Nichiren Shoshu (NST) are also of the Fuji

school lineage. Nichiren Shu and Kempon Hokke Shu are of the Minobu school lineage.

Nikko was emotionally attached to Nichiren and an ardent supporter of Nichiren’s most

radical ideas. The other elder priests seemed more emotionally connected to their

former schools of Buddhism than with what Nichiren taught. After Nichiren died, there

was some dispute between the priests. Nikko was appalled by the leniency of the other

elder priests toward practices and teachings contained in the earlier Buddhist scriptures,

which Nichiren had told them to discard. Nikko thus set out on his own to found a temple at

the base of Mount Fuji where he would propagate and practice a purer form of Nichiren Buddhism.

That’s getting ahead of ourselves, though. So far in this story, Nichiren has barely

even begun etching out his legacy.

During this seven-year period as an unknown street preacher in Kamakura, earthquakes,

floods, storms, famine, and epidemics ravaged Japan. Nichiren describes in his thesis

Rissho Ankoku Ron,

(trans. On Securing the Peace of the Land through the Propagation of True Buddhism),

“Famine and epidemics rage more fiercely than ever, beggars are everywhere in sight, and scenes of death

fill our eyes. Corpses pile up in mounds like observation platforms, and dead bodies lie side by side like planks on a bridge.”

In Japan at that time, the people and the government, everyone, thought that the fault of

natural disasters of this sort lay with the Emperor. The Emperor of Japan was also the spiritual

head of Japan, a descendent of the Shinto sun goddess. In other words, if the nation was in

turmoil, there was a religious cause. The government was quite concerned about the state of the

nation, and the emperor commissioned priests across the country to offer up prayers to help the situation,

but rather than getting better, things just kept getting worse and worse for the country.

After years of watching the government flail about seeking and not finding any solution to their woes,

in 1260

Nichiren decided to pen a letter to the government blaming the current state of affairs on their lack

of devotion to the Lotus Sutra and their greater devotion to inferior religions, particularly Nembutsu,

which he claimed was only making matters worse.

He further predicted that there would be foreign invasion and civil conflict.

This letter was called the Rissho Ankoku Ron.

The letter was far from his best writing, but it’s his most famous,

because it propelled his life onto a dangerous course which ultimately turned him into a folk legend.

There are a couple of reasons the Rissho Ankoku Ron is so famous.

For one, his predictions of war and conflict came true.

The other reason is that Nichiren so infuriated everyone with his criticisms of the government and other schools of

Buddhism, especially Nembutsu, that he came to be hated throughout the whole country.

He mentions this fact in several of his writings, for instance, in

A Sage Perceives the Three Existences of Life,

he writes “I, Nichiren, am the foremost sage in all Jambudvipa. Nevertheless, from the ruler on down to the

common people, all have despised and slandered me, attacked me with swords and staves, and even exiled me.”

He was so despised that the government and mobs of people attempted and failed to end his life several times.

One such incident was so significant that, had it not happened, no one would probably know Nichiren’s name today.

That incident is known as the Tatsunokuchi Persecution, but that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

In thirteenth century Japan, if the emperor endorsed your religion, that was a guarantee of success.

It was the ultimate prize of any chief priest to convert the emperor to your religion. Nichiren was

likely sincere in wanting the upheaval in the nation to end, but at the same time, it seems likely

that he had also hoped to obtain the notice of the government, win its endorsement, and found his own school of Buddhism.

He says in a letter entitled, The Actions of the Votary of the Lotus Sutra,

“If our land were governed by a

worthy ruler or sage sovereign, then the highest honors in Japan would be bestowed on me, and I

would be awarded the title of Great Teacher while alive. I had expected to be consulted about the Mongols, invited

to the war counsel, and asked to defeat them through the power of prayer.”

An endorsement from the government was not forthcoming. Quite the opposite, actually.

While officially they pretended to pay no heed to this insignificant street beggar,

unofficially a band of Nembutsu followers came to his hut and attempted to kill him. He

narrowly escaped with his life and hid away at the residence of one of his disciples,

Toki Jonin.

This incident is known as the Matsubagayatsu Persecution, named after the

location of his hut. Not one to while away precious life moments, he was soon back preaching

in Kamakura, where he was arrested.

By this time the Nembutsu priests had grown quite discomforted by this rabble-rousing

little priest from nowhere with his deep lectures on the Lotus Sutra, converting everyone

to his upstart form of Buddhism. They managed to convince the authorities to have him

exiled to the Izu Peninsula, where they sent troublemakers in the hope that they’d perish from

lack of food or shelter.

Fortunately, a couple that lived on Izu risked their own lives to care for Nichiren when he

first arrived. Several letters that he wrote to the couple over the course of his life still remain.

When the steward of the region became ill, some of the locals mentioned Nichiren. The steward

called on Nichiren to come to him and pray for his life. The steward recovered and converted,

which aided in Nichiren’s survival for his remaining time on Izu.

At the suggestion of the former regent, Hojo Tokiyori, who was the intended recipient of the

Rissho Ankoku Ron, Nichiren was pardoned and permitted to

return to Kamakura in 1263.

In 1264, Nichiren’s mother became ill.

He returned home to tend to his mother and pray for her recovery.

She recovered. Remember, though, that the steward of the area where he grew up, Tojo Kagenobu,

had wanted him arrested for the sermon he gave at the temple when he first returned home from his

15-year study trip. That must have been some speech, because Kagenobu was apparently still angry about it

11 years later. This time he and his samurai tried to kill Nichiren at Komatsubara, in an

incident called the Komatsubara Persecution.

Nichiren described the incident in one of his letters, Encouragement to a Sick Person:

Since their teachings are no match for mine, they resort to sheer force of numbers in trying to

fight against me. Nembutsu believers number in the thousands or ten thousands, and their supporters are many.

I, Nichiren, am alone, without a single ally. It is amazing that I should have survived until now.

This year, too, on the eleventh day of the eleventh month, between the hours of the monkey and the cock

(around 5:00 p.m.) on the highway called Matsubara in Tojo in the province of Awa, I was ambushed by several

hundred Nembutsu believers and others. I was alone except for about ten men accompanying me, only three or four of

whom were capable of offering any resistance at all. Arrows fell on us like rain, and swords descended like lightning.

One of my disciples was slain in a matter of a moment, and two others were gravely wounded. I myself sustained cuts and

blows, and it seemed that I was doomed. Yet, for some reason, my attackers failed to kill me; thus I

have survived until now.

Nichiren returned to Kamakura. In 1266, the Mongols sent a letter to Japan requesting that Japan become a

vassal of the Mongol empire or suffer the consequences. Japan didn’t respond. In 1268, the Mongols tried

again. Again, Japan didn’t respond. At the time, Kublai Khan had an insufficient navy to invade Japan,

so Japan had some time to strengthen reinforcements and prepare for the invasion while the Mongols worked

on their navy.

Meanwhile, the Japanese government was quite alarmed about the matter.

They called on the most eminent priests to pray for the safety of the nation.

Seeing his prophesy realized, Nichiren stepped up his correspondence with the government in an

attempt to convince them to heed his advice. His letters were ignored.

In 1271, the government ordered Ryokan, a chief priest of the True Word Precepts school,

to pray for rain during a drought.

Apparently, prior to the drought, Nichiren had gotten on Ryokan’s nerves by

creating doubt among Ryokan’s followers. Nichiren says in a letter he wrote on

behalf of his close disciple Shijo Kingo, “Whenever the priest Ryokan preached,

he would lament: ‘I am endeavoring to help all people in Japan become “observers of the precepts”

and to have them uphold the eight precepts…but Nichiren’s slander has prevented me

from achieving my desire.’”

When Nichiren heard that the government had asked Ryokan to pray for rain,

he decided to write Ryokan a challenge. He says that he conveyed this message to

Ryokan, “If the Honorable Ryokan brings about rainfall within seven days, I,

Nichiren, will stop teaching that the Nembutsu leads to the hell of incessant

suffering and become his disciple, observing the two hundred and fifty precepts.”

No rain fell, but instead gale force winds blew. It’s implied in Nichiren’s writings that

Ryokan accepted Nichiren’s challenge and agreed to become Nichiren’s disciple if Ryokan

lost the bet, but, though Ryokan was unable to make it rain, he never converted.

Rather than converting, he took steps to get rid of the pest. Nichiren explains

“In an attempt to have this sage executed, the Honorable Ryokan submitted a letter of

petition to the authorities proposing that he be beheaded.”

Hei no Saemon, a leading official of the Hojo regency,

summoned Nichiren to explain

himself against accusations leveled against him.

During the hearing, Nichiren made another

prophesy, one that would ultimately come true. “Within one hundred days after my exile or execution,

or within one, three, or seven years, there will occur what is called the calamity of internal strife,

rebellion within the ruling clan. This will be followed by the calamity of foreign invasion,

attack from all sides, particularly from the west. Then you will regret what you have done!”

Hei no Saemon did not appreciate Nichiren’s defiant attitude and had him arrested two days later.

Now we come to what is the most interesting and unusual (and famous) story in Nichiren’s life – his arrest,

attempted execution at Tatsunokuchi, and subsequent exile on Sado island. He tells the story the best

himself. All of the following story is taken from the autobiographical

letter entitled The Actions of the Votary of the Lotus Sutra.

On the twelfth day of the ninth month in the eighth year of Bun’ei (1271), cyclical sign kanoto-hitsuji,

I was arrested in a manner that was extraordinary and unlawful, even more outrageous than the arrest of

the priest Ryoko, who was actually guilty of treason, and the Discipline Master Ryoken, who sought to

destroy the government. Hei no Saemon led several hundreds of armor-clad warriors to take me.

Wearing the headgear of a court noble, he glared in anger and spoke in a rough voice. These actions were

in essence no different from those of the grand minister of state and lay priest, who seized power only to

lead the country to destruction.

Observing this, I realized it was no ordinary event and thought to myself,

“Over the past months I have expected something like this to happen sooner or later.

How fortunate that I can give my life for the Lotus Sutra! If I am to lose this worthless head

[for Buddhahood], it will be like trading sand for gold or rocks for jewels.”

Sho-bo, Hei no Saemon’s chief retainer, rushed up, snatched the scroll of the fifth

volume of the Lotus Sutra from inside my robes, and struck me in the face with it three times.

Then he threw it open on the floor. Warriors seized the nine other scrolls of the sutra, unrolled them,

and trampled on them or wound them about their bodies, scattering the scrolls all over the matting

and wooden floors until every corner of the house was strewn with them.

I, Nichiren, said in a loud voice, “How amusing! Look at Hei no Saemon gone mad! You gentlemen have

just toppled the pillar of Japan.” Hearing this, the assembled troops were taken aback. When they

saw me standing before the fierce arm of the law unafraid, they must have realized that they were

in the wrong, for the color drained from their faces.

………………………………………………………………………………………………

That night of the twelfth, I was placed under the custody of the lord of the province of Musashi and

around midnight was taken out of Kamakura to be executed. As we set out on Wakamiya Avenue, I looked

at the crowd of warriors surrounding me and said, “Don’t make a fuss. I won’t cause any trouble.

I merely wish to say my last words to Great Bodhisattva Hachiman.” I got down from my horse and called

out in a loud voice, “Great Bodhisattva Hachiman, are you truly a god? When Wake no Kiyomaro was about

to be beheaded, you appeared as a moon ten feet wide. When the Great Teacher Dengyo lectured on the Lotus

Sutra, you bestowed upon him a purple surplice as an offering. Now I, Nichiren, am the foremost votary of

the Lotus Sutra in all of Japan, and am entirely without guilt. I have expounded the doctrine to save all

the people of Japan from falling into the great citadel of the hell of incessant suffering for slandering

the Lotus Sutra. Moreover, if the forces of the great Mongol empire attack this country, can even the

Sun Goddess and Great Bodhisattva Hachiman remain safe and unharmed? When Shakyamuni Buddha expounded the

Lotus Sutra, Many Treasures Buddha and the Buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions gathered,

shining like so many suns and moons, stars and mirrors. In the presence of the countless heavenly gods as

well as the benevolent deities and sages of India, China, and Japan, Shakyamuni Buddha urged each one to

submit a written pledge to protect the votary of the Lotus Sutra at all times. Each and every one of you

gods made this pledge. I should not have to remind you. Why do you not appear at once to fulfill your solemn oath”?

Finally I called out: “If I am executed tonight and go to the pure land of Eagle Peak, I will dare to report to

Shakyamuni Buddha, the lord of teachings, that the Sun Goddess and Great Bodhisattva Hachiman are the deities

who have broken their oath to him. If you feel this will go hard with you, you had better do something about

it right away!” Then I remounted my horse.

Out on Yui Beach as the party passed the shrine there, I spoke again. “Stop a minute, gentlemen.

I have a message for someone living near here,” I said. I sent a boy called Kumao to Nakatsukasa

Saburo Saemon-no-jo [Shijo Kingo], who rushed to meet me. I told him, “Tonight,

I will be beheaded. This is something I have wished for many years. In this saha world,

I have been born as a pheasant only to be caught by hawks, born a mouse only to be eaten by cats,

and born human only to be killed attempting to defend my wife and children from enemies. Such things

have befallen me more times than the dust particles of the land. But until now, I have never given up my

life for the sake of the Lotus Sutra. In this life, I was born to become a humble priest, unable to adequately

discharge my filial duty to my parents or fully repay the debt of gratitude I owe to my country.

Now is the time when I will offer my head to the Lotus Sutra and share the blessings therefrom with my

deceased parents, and with my disciples and lay supporters, just as I have promised you.” Then the four men,

Saemon-no-jo and his brothers, holding on to my horse’s reins, went with me to Tatsunokuchi at Koshigoe.

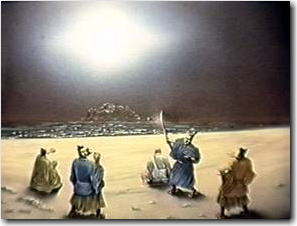

Tatsunokuchi Execution Attempt

Finally we came to a place that I knew must be the site of my execution. Indeed, the soldiers stopped and

began to mill around in excitement. Saemon-no-jo, in tears, said, “These are your last moments!” I replied,

“You don’t understand! What greater joy could there be? Don’t you remember what you have promised?” I had no

sooner said this when a brilliant orb as bright as the moon burst forth from the direction of Enoshima,

shooting across the sky from southeast to northwest. It was shortly before dawn and still too dark to see

anyone’s face, but the radiant object clearly illuminated everyone like bright moonlight. The executioner

fell on his face, his eyes blinded. The soldiers were filled with panic. Some ran off into the distance, some

jumped down from their horses and huddled on the ground, while others crouched in their saddles. I called out,

“Here, why do you shrink from this vile prisoner? Come closer! Come closer!” But no one would approach me.

“What if the dawn should come? You must hurry up and execute me—once the day breaks, it will be too ugly a job.”

I urged them on, but they made no response.

They waited a short while, and then I was told to proceed to Echi in the same province of Sagami. I replied that,

since none of us knew the way, someone would have to guide us there. No one was willing to take the lead,

but after we had waited for some time, one soldier finally said, “That’s the road you should take.”

Setting off, we followed the road and around noon reached Echi. We then proceeded to the residence of Homma Rokuro

Saemon. There I ordered sake for the soldiers. When the time came for them to leave, some bowed their heads,

joined their palms, and said in a most respectful manner: “We did not realize what kind of a man you are.

We hated you because we had been told that you slandered Amida Buddha, the one we worship. But now that we

have seen with our own eyes what has happened to you, we understand how worthy a person you are, and will

discard the Nembutsu that we have practiced for so long.” Some of them even took their prayer beads out of

their tinder bags and flung them away. Others pledged that they would never again chant the Nembutsu. After

they left, Rokuro Saemon’s retainers took over the guard. Then Saemon-no-jo and his brothers took their leave.

That evening, at the hour of the dog (7:00–9:00 p.m.), a messenger from Kamakura arrived with an order from the

regent. The soldiers were sure that it would be an official letter to behead me, but Uma-no-jo, Homma’s deputy,

came running with the letter, knelt, and said: “We were afraid that you would be executed tonight, but now the

letter has brought wonderful news. The messenger said that, since the lord of Musashi had left for a spa in Atami

this morning at the hour of the hare (5:00–7:00 a.m.), he set off at once and rode for four hours to get here

because he feared that something might happen to you. The messenger has left immediately to take news to the

lord in Atami tonight.” The accompanying letter read, “This person is not really guilty. He will shortly be pardoned.

If you execute him you will have cause to regret.”

Now it was the night of the thirteenth. There were scores of warriors stationed around my lodging and in the main garden.

Because it was the middle of the ninth month, the moon was very round and full. I went out into the garden and there,

turning toward the moon, recited the verse portion of the “Life Span” chapter. Then I spoke briefly about the faults of

the various schools, citing passages from the Lotus Sutra. I said: “You, the god of the moon, are Rare Moon, the son of a

god, who participated in the ceremony of the Lotus Sutra. When the Buddha expounded the ‘Treasure Tower’ chapter, you

received his order, and in the ‘Entrustment’ chapter, when the Buddha patted your head with his hand, in your vow you

said, ‘We will respectfully carry out all these things just as the World-Honored One has commanded.’ You are that very

god. Would you have an opportunity to fulfill the vow you made in the Buddha’s presence if it were not for me? Now that

you see me in this situation, you should rush forward joyfully to receive the sufferings of the votary of the Lotus Sutra

in his stead, thereby carrying out the Buddha’s command and also fulfilling your vow. It is strange indeed that you have

not yet done anything. If nothing is done to set this country to rights, I will never return to Kamakura. Even if you do

not intend to do anything for me, how can you go on shining with such a complacent face? The Great Collection Sutra says,

‘The sun and moon no longer shed their light.’ The Benevolent Kings Sutra says, ‘The sun and moon depart from their

regular courses.’ The Sovereign Kings Sutra says, ‘The thirty-three heavenly gods become furious.’ What about these

passages, moon god? What is your answer?”

Then, as though in reply, a large star bright as the Morning Star fell from the sky and hung in a branch of the plum

tree in front of me. The soldiers, astounded, jumped down from the veranda, fell on their faces in the garden, or ran

behind the house. Immediately the sky clouded over, and a fierce wind started up, raging so violently that the whole

island of Enoshima seemed to roar. The sky shook, echoing with a sound like pounding drums.

The day dawned, and on the fourteenth day, at the hour of the hare, a man called the lay priest Juro came and said to

me: “Last night there was a huge commotion in the regent’s residence at the hour of the dog. They summoned a

diviner, who said, ‘The country is going to erupt in turmoil because you punished that priest. If you do not

call him back to Kamakura immediately, there is no telling what will happen to this land.’ At that some said,

‘Let’s pardon him!’ Others said, ‘Since he predicted that war would break out within a hundred days, why don’t

we wait and see what happens.’”

I was kept at Echi for more than twenty days. During that period seven or eight cases of arson and an endless

succession of murders took place in Kamakura. Slanderers went around saying that Nichiren’s disciples were setting

the fires. The government officials thought this might be true and made up a list of over 260 of my followers who they

believed should be expelled from Kamakura. Word spread that these persons were all to be exiled to remote islands,

and that those disciples already in prison would be beheaded. It turned out, however, that the fires were set by the

observers of the precepts and the Nembutsu believers in an attempt to implicate my disciples. There were other things

that happened, but they are too numerous to mention here.

I left Echi on the tenth day of the tenth month (1271) and arrived in the province of Sado on the twenty-eighth day

of the same month. On the first day of the eleventh month, I was taken to a small hut that stood in a field called

Tsukahara behind Homma Rokuro Saemon’s residence in Sado. One room with four posts, it stood on some land where

corpses were abandoned, a place like Rendaino in Kyoto. Not a single statue of the Buddha was enshrined there;

the boards of the roof did not meet, and the walls were full of holes. The snow fell and piled up, never melting away.

I spent my days there, sitting in a straw coat or lying on a fur skin. At night it hailed and snowed, and there were

continual flashes of lightning. Even in the daytime the sun hardly shone. It was a wretched place to live.

Izu Peninsula and Sado Island

I felt like Li Ling, who was imprisoned in a rocky cave in the land of the northern barbarians, or the Tripitaka

Master Fa-tao, who was branded on the face and exiled to the area south of the Yangtze by Emperor Hui-tsung.

Nevertheless, King Suzudan received severe training under the seer Asita to obtain the blessings of the Lotus Sutra,

and even though Bodhisattva Never Disparaging was beaten by the staves of arrogant monks and others, he achieved

honor as votary of the one vehicle. Therefore, nothing is more joyful to me than to have been born in the Latter Day

of the Law and to suffer persecutions because I propagate the five characters of Myoho-renge-kyo. For more than

twenty-two hundred years after the passing of the Buddha, no one, not even the Great Teacher T’ien-t’ai Chih-che,

experienced the truth of the passage in the sutra that says, “It [the Lotus Sutra] will face much hostility in the

world and be difficult to believe.” Only I have fulfilled the prophecy from the sutra, “again and again we will be

banished.” The Buddha says, in reference to those who “listen to one verse or one phrase [of the Lotus Sutra of the

Wonderful Law],” that “I will bestow on all of them a prophecy [that they will attain supreme perfect enlightenment].”

Thus there can be no doubt that I will reach supreme perfect enlightenment. It is the lord of Sagami above all who has

been a good friend to me. Hei no Saemon is to me what Devadatta was to Shakyamuni Buddha. The Nembutsu priests are

comparable to the Venerable Kokalika, and the observers of the precepts to the monk Sunakshatra. The age of the Buddha

is none other than today, and our present age is none other than that of the Buddha. This is what the Lotus Sutra describes

as the “true aspect of all phenomena” and as “consistency from beginning to end.”

………………………………………………………………………………………………

In the yard around the hut the snow piled deeper and deeper. No one came to see me; my only visitor was

the piercing wind. Great Concentration and Insight

and the Lotus Sutra lay open before my eyes,

and Nam-myoho-renge-kyo flowed from my lips. My evenings passed in discourse to the moon and

stars on the fallacies of the various schools and the profound meaning of the Lotus Sutra.

Thus, one year gave way to the next.

One finds people of mean spirit wherever one goes. The rumor reached me that the observers

of the precepts and the Nembutsu priests on the island of Sado, including Yuiamidabutsu,

Shoyu-bo, Insho-bo, Jido-bo, and their followers—several hundred of them—had met to decide

what to do about me. One said: “Nichiren, the notorious enemy of Amida Buddha and an evil

teacher to all people, has been exiled to our province. As we all know, exiles to this

island seldom manage to survive. Even if they do, they never return home. So no one is

going to be punished for killing an exile. Nichiren lives all alone at a place called Tsukahara.

No matter how strong and powerful he is, if there’s no one around, what can he do? Let’s go together

and shoot him with arrows!” Another said, “He was supposed to be beheaded, but his execution has been

postponed for a while because the wife of the lord of Sagami is about to have a child. The postponement

is merely temporary, though. I hear he is eventually going to be executed.” A third said, “Let’s ask

Lord Rokuro Saemon to behead him. If he refuses, we can plan something ourselves.” There were many

proposals about what to do with me, but the third proposal [mentioned above] was decided on.

Eventually several hundred people gathered at the constable’s office.

Rokuro Saemon addressed them, saying: “An official letter from the regent directs that the priest shall not

be executed. This is no ordinary, contemptible criminal, and if anything happens to him, I, Shigetsura,

will be guilty of grave dereliction. Instead of killing him, why don’t you confront him in religious debate?”

Following this suggestion, the Nembutsu and other priests, accompanied by apprentice priests carrying the three

Pure Land sutras, Great Concentration and Insight, the True Word sutras, and other literature under their arms

or hanging from their necks, gathered at Tsukahara on the sixteenth day of the first month [in 1272]. They came

not only from the province of Sado but also from the provinces of Echigo, Etchu, Dewa, Mutsu, and Shinano.

Several hundred priests and others gathered in the spacious yard of the hut and in the adjacent field.

Rokuro Saemon, his brothers, and his entire clan came, as well as lay priest farmers, all in great numbers.

The Nembutsu priests uttered streams of abuse, the True Word priests turned pale, and the Tendai priests

called loudly to vanquish the opponent. The lay believers cried out in hatred, “There he is—the notorious

enemy of our Amida Buddha!” The uproar and jeering resounded like thunder and seemed to shake the earth.

I let them clamor for a while and then said, “Silence, all of you! You are here for a religious debate.

This is no time for abuse.” At this, Rokuro Saemon and others voiced their accord, and some of them grabbed

the abusive Nembutsu followers by the neck and pushed them back.

The priests proceeded to cite the doctrines of Great Concentration and Insight and the True Word and the

Nembutsu teachings. I responded to each, establishing the exact meaning of what had been said, then coming

back with questions. However, I needed to ask only one or two at most before they were completely silenced.

They were far inferior even to the True Word, Zen, Nembutsu, and Tendai priests in Kamakura, so you can

imagine how the debate went. I overturned them as easily as a sharp sword cutting through a melon or a gale

bending the grass. They not only were poorly versed in the Buddhist teachings but contradicted themselves.

They confused sutras with treatises or commentaries with treatises. I discredited the Nembutsu by telling how

Shan-tao fell out of the willow tree, and refuted the story about the Great Teacher Kobo’s three-pronged

diamond-pounder and of how he transformed himself into the Thus Come One Mahavairochana. As I demonstrated

each falsity and aberration, some of the priests swore, some were struck dumb, while others turned pale.

There were Nembutsu adherents who admitted the error of their school; some threw away their robes and beads

on the spot and pledged never to chant the Nembutsu again.

The members of the group all began to leave, as did Rokuro Saemon and his men. As they were walking across the

yard, I called the lord back to make a prophecy. I first asked him when he was departing for Kamakura, and

he answered that it would be around the seventh month, after his farmers had finished their work in his fields.

Then I said: “For a warrior, ‘work in the fields’ means assisting his lord in times of peril and receiving fiefs

in recognition of his service. Fighting is about to break out in Kamakura. You should hasten there to distinguish

yourself in battle, and then you will be rewarded with fiefs. Since your warriors are renowned throughout the

province of Sagami, if you remain here in the countryside tending to your farms and arrive too late for the

battle, your name will be disgraced.” I do not know what he thought of this, but Homma, dumbfounded, did not

utter a word. The Nembutsu priests and the observers of the precepts and lay believers looked bewildered, not

comprehending what I had said.

After everyone had gone, I began to put into shape a work in two volumes called

The Opening of the Eyes,

which I had been working on since the eleventh month of the previous year. I wanted to record the wonder of

Nichiren, in case I should be beheaded. The essential message in this work is that the destiny of Japan

depends solely upon Nichiren. A house without pillars collapses, and a person without a soul is dead.

Nichiren is the soul of the people of this country. Hei no Saemon has already toppled the pillar of Japan,

and the country grows turbulent as unfounded rumors and speculation rise up like phantoms to cause dissention

in the ruling clan. Further, Japan is about to be attacked by a foreign country, as I described in my

On Establishing the Correct Teaching. Having written to this effect, I entrusted the manuscript to

Nakatsukasa Saburo Saemon-no-jo’s messenger. The disciples around me thought that what I had written was

too provocative, but they could not stop me.

Just then a ship arrived at the island on the eighteenth day of the second month. It carried the news that

fighting had broken out in Kamakura and then in Kyoto, causing indescribable suffering. Rokuro Saemon,

leading his men, left on fast ships that night for Kamakura. Before departing, he humbly begged for my assistance

with palms joined.

He said: “I have been doubting the truth of the words you spoke on the sixteenth day of last month, but they have

come true in less than thirty days. I see now that the Mongols will surely attack us, and it is equally certain

that believers in Nembutsu are doomed to the hell of incessant suffering. I will never chant the Nembutsu again.”

~ Nichiren, The Actions of the Votary of the Lotus Sutra

The intent behind sending Nichiren, or anyone, to Sado was to kill him. Anyone caught helping him was subject to

imprisonment or death. However, people did secretly help him and he managed to barely survive. Somehow, he did have

his ever faithful follower with him, Nikko.

His near execution and subsequent exile was a benefit in disguise for him and humanity.

Nichiren’s time on Sado was the peak of his teaching life. Because of his near execution at Tatsunokuchi,

referred to as the Tatsunokuchi Persecution, he was inspired by a sense of urgency and mission.

He says in one letter, “I was very nearly beheaded at Tatsunokuchi. From that time, I felt pity for

my followers because I had not yet revealed this true teaching to any of them.”

His most important writings were penned while in exile on Sado Island, including the work he mentioned in his autobiographical

account quoted above, The Opening of the Eyes,

as well as The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind,

The Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life,

The True Aspect of All Phenomenon,

Letter from Sado, and others.

It isn’t entirely covered in this version of his life story, but there is a mythology around Nichiren.

Many bizarre stories about Nichiren have been passed down to this day. The stories range from the

likely to the possible to the totally implausible. He is said, for instance, to have had mystical control over dragons.

We have limited our story to what has been recorded in writings in his own hand or in the hand of his own disciples

from the time period that are known to have occurred or seem likely to have occurred given the circumstances.

Other strange stories we have not mentioned are at least plausible and therefore may have indeed occurred.

As it is, even the stories we did include seem mysterious enough without having to embellish his legend any further.

We think even with our limited telling of his life, the reader can get some idea of the nature of events that surrounded him.

We don’t know what exactly was being spread about Nichiren at the time, but even going by his own accounts of what happened,

he seemed to have a sort of uncanny ability to sense what was on the horizon, to protect himself, and to inspire awe.

The purpose of mentioning this isn’t to add to his legend but to highlight the atmosphere and the image of him in the

minds of the people around him. People seemed to both revile him and respect him at the same time. While on Sado,

he was causing quite a stir, as he did where ever he went. As can be seen by the story above, he made uncanny

predictions, and strange occurrences seemed to follow him around. He developed a reputation on the island for

having supernatural powers.

He thought he was quite good at making predictions, but as one can see from reading his writings, he was always

certain he was going to be killed at any moment. He lived in constant fear for his life. Yet, to his own constant

amazement, he always managed to somehow escape death. (That is, of course, until he died.) He wanted to create the

illusion of being wise about the ways of the world, and therefore able to make predictions. However, he wasn’t trying

to create the illusion of being able to manipulate the world with his mind. He did that by sheer accident.

If it weren’t for that, his more profound and complex teachings probably wouldn’t have survived to this day as they have.

Adding to the strangeness of his character, he would yell at the sun and moon from atop hilltops where others could hear him.

And he would throw statues of Amida Buddha into the river.

Getting back to the story, because Nichiren’s legend was spreading, and because the people began to fear his special powers,

the people of Sado stopped supporting the Nembutsu temples and priests. It was causing distress to the priests on the island,

so they contrived to have him removed from the island.

It didn’t work at first. The first thing they did was imprison anyone that was even thought to be a follower of his

or who so much as walked past his hut.

That measure failing, they ultimately had him pardoned just to get rid of him.

In 1274, he was pardoned from exile and returned to Kamakura.

Hei no Saemon asked to meet with him again. This time Hei no Saemon wasn’t angry.

He instead sincerely consulted with Nichiren about various Buddhist teachings.

Then he asked Nichiren when the Mongol forces were to invade.

Nichiren said that they would arrive by the end of the year. At the same time,

he reiterated his warning that they should subscribe only to the Lotus Sutra and not to any

other Buddhist teaching.

Hei no Saemon let Nichiren carry on with his life, but he did not heed Nichiren’s

suggestion about the Lotus Sutra. The Mongols did attempt to invade by the end of the year,

arriving on October 5, 1274.

The islands of Iki and Tsushima were captured.53

However, after their first two conquests, most of the Mongol naval forces were swept away by a

sudden typhoon, and the forces that were left were easily overwhelmed by Japanese samurai.

That did not stop the Mongols from making another attempt in 1281.

It’s clear in the telling that Nichiren lived the life of a sort of mystical person, a messiah.

He performed miraculous deeds and was protected from his enemies by the natural world.

Most Nichiren Buddhists read a message into that life, so it’s necessary to stop here

and say something about the nature of his life story and what that has to do with our

philosophy and practice of Buddhism.

Nichiren himself believed in gods, protective deities, which may or may not have been literal

figures in his mind. He at least believed that through his Buddhist practice he had some measure

of control over the environment around him. He believed that by practicing Buddhism, he could turn

the environment into a Buddha land. That is the primary teaching of Nembutsu. He simply didn’t

believe that it could be accomplished by praying to Amida.

He didn’t seem to know exactly how much control he had as an individual. He argued in the

Rissho Ankoku Ron that the nation would be protected from natural disasters and other hardships

by practicing the Lotus Sutra, but he didn’t seem quite as sure that as individuals in a

non-Lotus-Sutra-Buddhist country that he and his disciples would be protected, as was evidenced by

their many persecutions, including their deaths. He seemed genuinely surprised every time he

survived an attempt on his own life.

He also clearly believed that he could predict the future through a reading of the Buddhist scriptures.

So the question would be put to us whether in the telling of this story we’re advocating a practice of

Protection Buddhism or Prophesy Buddhism. The answer is an unequivocal no, but we must then answer for

Nichiren’s life story.

First, we don’t think there’s any hard evidence that Nichiren had any special ability to foresee the future.

On the matter of general internal strife as described in the Rissho Ankoku Ron,

that was almost inevitable.

It was Japan, the land of the samurai clans. What are the odds that at some point in Nichiren’s life there

would not be internal strife?

On the matter of foreign invasion, the Mongol Empire was marching across Eurasia, so it was only a matter of time

before Japan would be next.

That having been said, this practice of Buddhism, chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo,

deepens one's wisdom and ability to see things others may not be able to see and to make causal connections that

others overlook. The fact that the pieces were already in place for anyone to be able to see in retrospect

doesn't mean that Nichiren's ability to put the pieces together, while maybe not supernatural, isn't

meaningful or significant. It wasn't beyond the scope of human intelligence to see these things coming, but

no one else saw them.

We would say that Nichiren was able to summon up wisdom not because he was a supernatural messiah but because

he chanted to a point of having a deeper understanding of the fundamental mechanics life.

Though there are ways he could have gleaned his predictions from information known to him,

it takes wisdom to be able to see a truth through a cacophony of noise.

In other words, he developed his wisdom through his practice of Buddhism.

Even more than that, we do think there is an extra sense of the world that one achieves through meditation.

There’s an increased sensitivity to the outside world, to a collective consciousness. We think Nichiren

was likely able to pick up on and interpret vibes coming from the world around him that others were unable to tap.

As an example of what we mean, the light bulb is said to have been invented in several places around the world

at the same time. In fact, several inventions were. There appears tobe a sort of connection in the world leading

humanity to think similar kinds of thoughts at the same time. Nichiren was especially sensitive to this connection

through his practice of Buddhism.

We don’t have a point of view on protection Buddhism, except to say that it’s probably best not to rely too heavily on it.

Keep in mind that though Nichiren may have survived, many of his disciples did not.

More to the point than any of this is that Nichiren’s own practice of Buddhism and his own teachings were

almost entirely about attaining Buddhahood. Practicing Buddhism on the basis of the story of his life

veers us off track from the message he tried to propagate, which is that the purpose of Buddhism is to attain

enlightenment, and that ought to be our sole focus, as it was his.

In December 1274, Nichiren retired to Mount Minobu,

saying “If a worthy man makes three attempts to warn the

rulers of the nation and they still refuse to heed his advice, then he should retire to a mountain forest.

This has been the custom from ages past, and I have accordingly followed it.”54

He spent the remaining years of his life there training his priests and writing letters to disciples.

Nichiren wrote about his teacher, Dozen-bo, who instructed him when Nichiren was a

teenager at Seicho-ji temple, in a letter entitled

Flowering and Bearing Grain,

If a tree is deeply rooted, its branches and leaves will never wither.

If the spring is inexhaustible, the stream will never run dry. Without wood,

a fire will burn out. Without earth, plants will not grow. I, Nichiren, am indebted

solely to my late teacher, Dozen-bo, for my having become the votary of the Lotus Sutra

and my being widely talked about now, in both a good and bad sense. Nichiren is like the

plant, and my teacher, the earth…. The blessings that Nichiren obtains from propagating the

Lotus Sutra will always return to Dozen-bo. How sublime! It is said that, if a teacher has a

good disciple, both will gain the fruit of Buddhahood, but if a teacher fosters a bad disciple,

both will fall into hell. If teacher and disciple are of different minds, they will never accomplish anything.

It’s clear from this passage that Nichiren considered Dozen-bo his teacher who is responsible for

him having “become the votary of the Lotus Sutra.” Nichiren was even considered Dozen-bo’s

favorite pupil. However, it’s interesting to note that though Dozen-bo taught Nichiren as a boy,

and though they had a strong bond with each other, Dozen-bo never practiced Nichiren’s version of Buddhism,

and Nichiren didn’t practice Dozen-bo’s. In the end, Nichiren surpassed Dozen-bo, and though Dozen-bo didn’t

follow him, Nichiren carried on with his teaching without him.

In one writing, The Tripitaka Master Shan-wu-wei,

Nichiren describes a meeting with Dozen-bo in which Nichiren,

having been parted from his teacher for so long and fearful that this may be his last opportunity to speak with him,

scolds Dozen-bo for robotically practicing the Nembutsu because everyone else did it.

Nichiren quoted Dozen-bo in

this encounter as saying, “But because this practice has become so widespread in our time, I simply repeat like others

the words Namu Amida Butsu.”

Nichiren goes on to explain his rationale for arguing with his own teacher,

saying, “At that time I certainly had no thought of quarreling with him…. I thought that the proper and courteous

thing would be to reason with him in mild terms and to speak in a gentle manner…. On the other hand, …it occurred to

me that I might never again have another opportunity to meet with him…. I was filled with pity for him and therefore

made up my mind to speak to him in very strong terms.”

One may not wind up rejecting the views of one’s teacher, but blind adherence to one’s teacher isn’t an appropriate

relationship to have, either. Nichiren said that the best way to repay the debt of gratitude one owes to one’s teacher

is to simply have faith in the Lotus Sutra. That way the results of the student’s causes naturally flow back in time,

in the link of causation, to one’s teacher, who helped point one toward the path, intentionally or otherwise.

He says the same about one’s parents and even one’s enemies:

All these things I have done solely to repay the debt I owe to my parents, the debt I owe to my teacher, the debt

I owe to the three treasures of Buddhism, and the debt I owe to my country. For their sake I have been willing

to destroy my body and to give up my life, though as it turns out, I have not been put to death after all….

Through this merit I will surely lead to enlightenment my parents and my teacher, the late Dozen-bo.

As can be seen from his life story, Nichiren faced many perils throughout his lifetime from angry believers of other

schools of Buddhism, but he wasn’t alone. His followers, too, faced all manner of major and minor persecutions as well,

from having their land confiscated to being imprisoned or killed. In several letters he expressed concern for the

well-being and safety of his followers and sometimes told them to be careful around others or to not tell people they’re

followers of his in the first place so as to avoid harm.

He couldn’t always protect them, though. In one incident, known as the Atsuhara Persecution, some of his followers from

Atsuhara, who were under Nikko’s tutelage, were arrested, tortured and beheaded. In the face of persecution during this

trial, Nichiren’s disciples stood by each other, helped each other, and all were firm in their resolve to remain followers

of Nichiren to the end.

Nichiren was deeply moved by them. During this time, he wrote one of his most well-known passages,

“Although Nichiren and his followers are few, because they are different in body, but united in mind, they will

definitely accomplish their great mission of widely propagating the Lotus Sutra. Though evils may be numerous,

they cannot prevail over a single great truth, just as many raging fires are quenched by a single shower of rain.

This principle also holds true with Nichiren and his followers.”

In 1282,

Nichiren attempted to travel to a hot spring to help relieve an illness he was suffering from,

but he died along the way.

The important takeaway from Nichiren’s life story isn’t that he possessed magic or supernatural

powers to control the natural world. Rather, he himself preferred to focus on the fact that he unwaveringly

dedicated his life to the mission of propagating Buddhism and to the enlightenment of the people of

Japan (and by extension in modern times, the whole world). Nichiren wrote often that his outlook on his own

persecutions was that he was prepared and willing to offer his life for the sake of his own and others’

enlightenment.

In his letter, Persecution at Tatsunokuchi, he writes to Shijo Kingo:

At the time of my persecution on the twelfth, not only did you accompany me to Tatsunokuchi,

but also you declared that you would die by my side. This can only be called wondrous.

How many are the places where I have thrown away my life in past existences for the sake of my wife and

children, lands and followers! I have given up my life on the mountains and the seas, on the rivers, on

the seashore, and by the roadside. Never once, however, did I die for the Lotus Sutra or suffer persecution

for the daimoku. Hence none of the ends I met enabled me to attain Buddhahood. Because I did not attain

Buddhahood, the seas and rivers where I threw away my life are not Buddha lands.

In Questions and Answers about Embracing the Lotus Sutra, he writes:

Life lasts no longer than the time the exhaling of one breath awaits the drawing of another. At what time,

what moment, should we ever allow ourselves to forget the compassionate vow of the Buddha,

who declared, “At all times I think to myself: [How can I cause living beings to gain entry into the

unsurpassed way and quickly acquire the body of a Buddha]?” On what day or month should we permit ourselves to

be without the sutra that says, “[If there are those who hear the Law], then not a one will fail to attain Buddhahood”?

How long can we expect to live on as we have, from yesterday to today or from last year to this year?

We may look back over our past and count the years we have accumulated, but when we look ahead into the future,

who can for certain number himself among the living for another day or even for an hour? Yet, though one may know

that the moment of one’s death is already at hand, one clings to arrogance and prejudice, to worldly fame and profit,

and fails to devote oneself to chanting the Mystic Law.

The following passage is from Nichiren’s doctrinal thesis The Opening of the Eyes:

If I were to falter in my determination in the face of persecutions by the sovereign, however, it would

be better not to speak out. While thinking this over, I recalled the teachings of the “Treasure Tower”

chapter on the six difficult and nine easy acts. Persons like myself who are of paltry strength might still be

able to lift Mount Sumeru and toss it about; persons like myself who are lacking in supernatural powers might

still shoulder a load of dry grass and yet remain unburned in the fire at the end of the kalpa of decline;

and persons like myself who are without wisdom might still read and memorize as many sutras as there are

sands in the Ganges. But such acts are not difficult, we are told, when compared to the difficulty of embracing

even one phrase or verse of the Lotus Sutra in the Latter Day of the Law. Nevertheless, I vowed to summon up a

powerful and unconquerable desire for the salvation of all beings and never to falter in my efforts.

It is already over twenty years since I began proclaiming my doctrines. Day after day, month after month,

year after year I have been subjected to repeated persecutions. Minor persecutions and annoyances are too

numerous even to be counted, but the major persecutions number four. Among the four, twice I have been subjected to

persecutions by the rulers of the country. The most recent one has come near to costing me my life.

In addition, my disciples, my lay supporters, and even those who have merely listened to my teachings

have been subjected to severe punishment and treated as though they were guilty of treason….

The more the government authorities rage against me, the greater is my joy. For instance, there

are certain Hinayana bodhisattvas, not yet freed from delusion, who draw evil karma to themselves

by their own compassionate vow. If they see that their father and mother have fallen into hell and

are suffering greatly, they will deliberately create the appropriate karma in hopes that they too may

fall into hell and share in and take their suffering upon themselves. Thus suffering is a joy to them.

It is the same with me….

This I will state. Let the gods forsake me. Let all persecutions assail me. Still I will give my life

for the sake of the Law. Shariputra practiced the way of the bodhisattva for sixty kalpas, but he

abandoned the way because he could not endure the ordeal of the Brahman who begged for his eye….

Here I will make a great vow. Though I might be offered the rulership of Japan if I would only abandon the

Lotus Sutra, accept the teachings of the Meditation Sutra, and look forward to rebirth in the Pure Land,

though I might be told that my father and mother will have their heads cut off if I do not recite the

Nembutsu—whatever obstacles I might encounter, so long as persons of wisdom do not prove my teachings to

be false, I will never yield! All other troubles are no more to me than dust before the wind.

will be the pillar of Japan. I will be the eyes of Japan. I will be the great ship of Japan.

This is my vow, and I will never forsake it!

He attempted to infuse this same sense of unflagging determination and dedication in his disciples,

and indeed he passed it down to Nikko, who promoted it as a key aspect of his branch of Buddhism.